Interpretive texts for exhibitions are arguably the least popular literary genre. At least, that is what you might conclude from the Survey of Joys and Pains of Visitors to Czech Museums and Galleries, which we conducted at the end of last year. The data show that four out of five visitors struggle with curatorial labels. Respondents even identified them as the sixth most pressing problem they encounter during a museum visit.

What makes these texts so challenging that even “ticket prices being too high” or “inconvenient opening hours” are perceived as smaller barriers to visiting a museum? First, it is worth noting that only 12% of the adult population across OECD countries can comfortably read and interpret long, complex texts. Simplified audio storytelling can therefore be significantly more accessible for visitors.

No single story fits everyone

A substantial part of the problem lies in the fact that the same exhibition is visited by people who differ widely in expectations, mood, knowledge or age. Trying to address them all with one universal narrative is as difficult as writing a book that appeals to every reader—or making a film that delights every viewer.

Objects cannot tell stories on their own – they need an intermediary. And when that intermediary is just a single, unified text, it inevitably fails to serve everyone. Creating one narrative that resonates equally with a bored teenager on a school trip and a university professor with deep expertise in the subject is difficult, if not impossible. And even if such a text could somehow exist, would it also engage parents with small children, who perceive the exhibition mainly as a backdrop for their afternoon programme? The introverted art student looking for metaphors and hidden meanings? The German tourist ticking off a “must-see” cultural attraction? Or the grant committee member who must be convinced of the project’s academic merit?

Even this brief list suggests that a “one-text-fits-all” solution is unlikely to work.

A story that knows how to adapt

So what can be done? Ideally, every visitor should have the opportunity to experience an exhibition through a personalised narrative. This is precisely what good museum educators and guides strive for—they adapt their storytelling to the specific people they are guiding. Yet such skilled and empathetic storytellers are rare, and encountering them is far from a standard part of the museum experience.

How, then, can tailored storytelling become accessible to everyone?

At Cabinet of Wonders we focus on developing mobile guides that take advantage of artificial intelligence in various ways—automated translations, recommendations of exhibits and points of interest, or text-to-speech conversion. We also explore how this technology might support personalised storytelling.

Cabinet Storyteller

Our latest experiment, Cabinet Storyteller, does exactly that. It is a prototype in which you first select the visitor’s persona—their language, age and main interest. Then you choose who will act as the narrator: a museum curator, the artwork’s creator, or perhaps its original owner. Finally, you select an exhibit and click “Generate Story”. Within seconds, a text is produced based on factual information about the object, with its style, tone and depth adjusted to the chosen parameters.

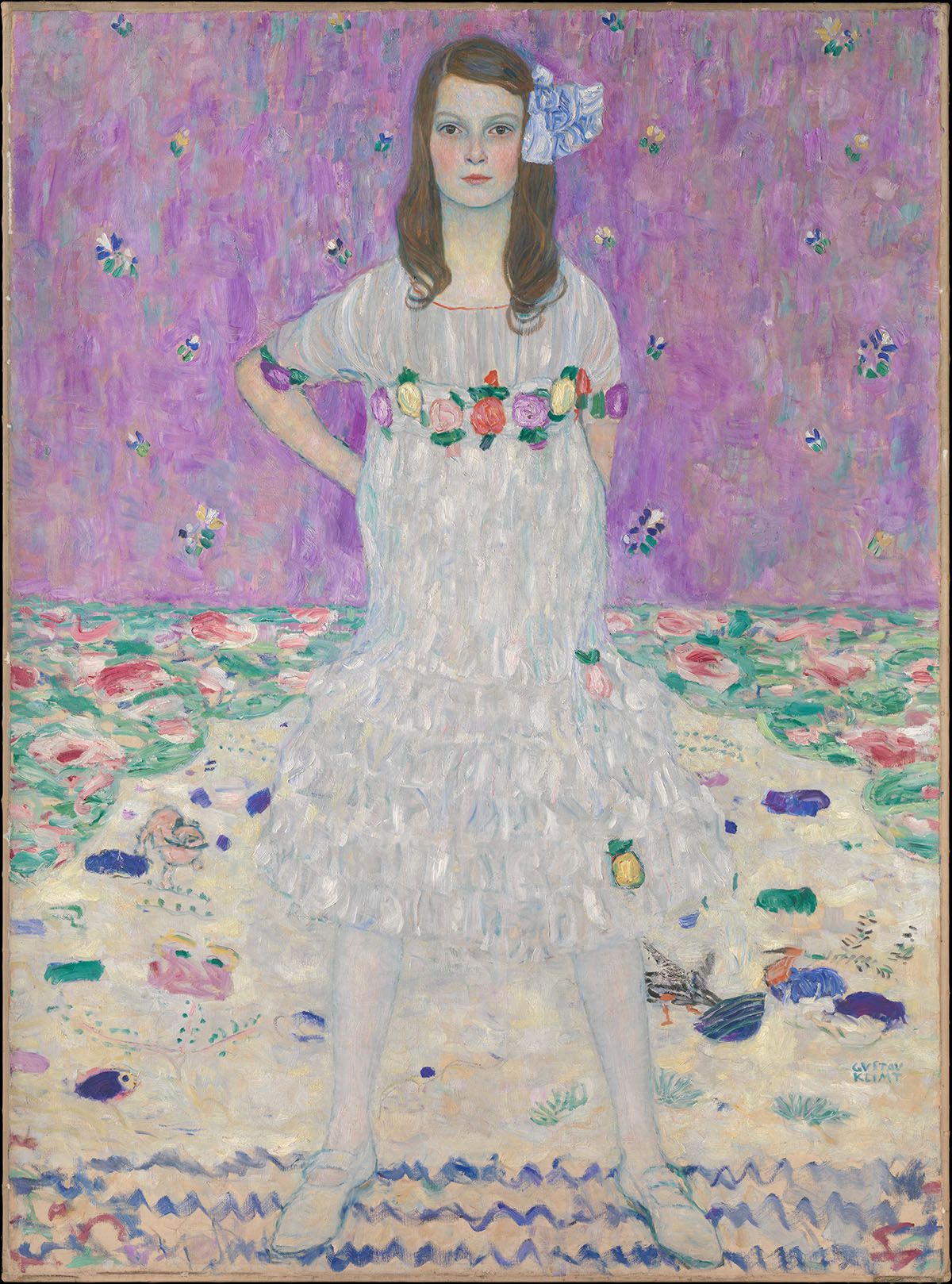

Here are examples of several different outputs—all generated for Gustav Klimt’s painting Portrait of Mäda Primavesi:

Mäda Primavesi (1903–2000), Gustav Klimt, 1912–13, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Visitor: English, Young child under 8, interested in playing games

Narrator: Museum curator

Hi there, come and take a look at this beautiful painting! It’s called “Mäda Primavesi” and it was painted by the famous artist Gustav Klimt. Do you see the girl in the colourful dress? She was only nine years old, but she stands here with great confidence, almost like a heroine from a fairy tale! Klimt played around with the picture a lot, trying different poses and colours before he came up with this cheerful scene full of floral patterns. Do you think you would like to pose in such a beautiful dress too?

Visitor: English, Young adult (18–29), interested in fine art

Narrator: The artist

Welcome, my young friend. I am Gustav Klimt, and I would like to introduce you to my portrait of little Mäda Primavesi, which I worked on between 1912 and 1913. Look at how confidently nine-year-old Mäda stands here – it is not typical for a girl of her age, but she truly had an exceptionally energetic and independent spirit. I carefully experimented with different poses, dresses and backgrounds to capture her personality, as well as the taste of her family, who were major patrons of modern art in Vienna. Notice the lively spring patterns in her dress and in the surroundings – they symbolise freshness and the new energy of my time.

Visitor: English, Adult (30–64), interested in history

Narrator: Original owner

Welcome, esteemed visitor. My name is Otto Primavesi, and allow me to introduce this remarkable portrait of my daughter Mäda, created for us by the renowned Gustav Klimt in 1913. My wife Eugenia and I were great admirers of modern Viennese culture – which is precisely why we wanted Mäda’s portrait to be not only a depiction of her likeness, but also a reflection of our time: fresh, bold, and open to new ideas. Look at the confidence – and perhaps even the audacity – with which Mäda stands here in her specially tailored dress, surrounded by floral patterns that evoke both spring and the turbulent spirit of youth. This painting is not only a testament to our taste, but also a record of our family’s social standing.

The curator becomes a prompt engineer

Formulating prompts and parameters is a highly interpretative task. In Cabinet Storyteller, for example, we defined the narrator instructions as follows:

- Collector: Act as a collector who owns this object. Mention the author and explain why their work is valuable or appealing to you. Express an emotional connection to the object (e.g. “I particularly like this detail…”, “I am always fascinated by how…”).

- Artist: Act as the creator of the work and naturally refer to yourself (“I created this… / my workshop…”). Introduce yourself or your workshop. Explain your profession. Provide details on when and where the piece was created.

- Original owner: Act as the first owner or the commissioner of the work. State your social status. Mention that the work was created by the given artist and explain why you commissioned it.

- Curator: Act as a curator and expert on the subject. Briefly introduce the artist or workshop and explain the cultural or artistic significance of their work.

And here are the age parameters we defined:

- Young child: “The visitor is about seven years old. Use informal, short and playful sentences (6–10 words). Use second-person informal address.”

- Older child: “The visitor is about ten years old. Use an informal, lively tone, include one interesting fact, encourage the visitor to observe details. Use second-person informal address.”

- Teenager: “The visitor is about fifteen. Use an energetic, informal tone; where natural, link to pop culture. Use second-person informal address.”

- …

Based on the visitor’s characteristics, the application composes a structured prompt in the background, which is then sent to the language model. The resulting story is the model’s response to this prompt.

In today’s museum practice, a curator or educator typically presents their interpretation through a single, unified narrative. Creating personalised narratives changes this framework—museum staff cannot realistically prepare a unique story for each visitor. Yet this does not mean curators lose their role in shaping the storytelling. Instead, their task becomes defining the parameters and prompts from which the narrative is generated. In this way, they retain control over meaning while enabling personalised communication.

The curator becomes a prompt engineer.

Try Cabinet Storyteller

The best way to understand its potential—and its current limitations—is simply to try Cabinet Storyteller yourself.

Technical solution

Cabinet Storyteller works with open data provided by the Cleveland Museum of Art. After selecting a topic, the system automatically downloads several randomly chosen digital reproductions from the relevant collection. These reproductions include images and metadata, with the metadata containing factual information about the object and, in some cases, a factual curatorial note.

The storytelling itself is generated using OpenAI’s GPT-4o language model, based on factual object data, the chosen visitor and narrator parameters, and system prompts that determine the story’s style and formal structure. Once generated, the text is sent to the ElevenLabs Flash v2.5 text-to-speech model, which converts it into spoken audio.

---

Cabinet Storyteller was created by Lukáš Pilka and the Cabinet of Wonders team in 2025.